Late Stage RINGS OF POWER

Can orcs be dads? Is Celebrimbor gay? Have we exhausted our current system of corporate nerddom?

Thanks for reading! If you share this piece, please credit it simply to Muse from the Orb. For various reasons, I’ll be known simply as orb_muse from now on.

They say God stays in heaven because He fears what He’s created, and to that I say, cool. Two seasons of The Rings of Power have convinced me God should stay out of our business, actually; the people who write Rings of Power in a windowless conference room at Amazon can take it from here. As the inevitable corporate singularity spreads toward the horizon, and our human shells are hooked up to an endless feed of shows like this, I think that we could stand to marvel more at these vast images we have been given. My roommate asked, “Are the dwarves digging down to get to sunlight?” They were.

I’ve decided that we can’t judge Rings of Power on a human scale; perhaps not even on the scale of the aforementioned God. As a piece of art, it’s far too baffling. The deeper you stare, the more it starts to feel like some non-Euclidean artifact from a Lovecraft story staring back at you. What does this dialogue mean? Why did they switch to iambic pentameter for this speech? He’s just called “The Dark Wizard”? Last season, when Galadriel’s brother Finrod turned to her in the very first episode and said

Do you know why a ship floats and a stone cannot? Because the stone sees only downward. The darkness of the water is vast and irresistible. The ship feels the darkness as well, striving moment by moment to master her and pull her under. But the ship has a secret. For unlike the stone, her gaze is not downward but up. Fixed upon the light that guides her, whispering of grander things than darkness ever knew

my soul left my body and floated awhile against the border of some tessellated realm as far beyond our comprehension as computer circuits are to ants’. You know how inmates trapped in solitary confinement start to lose their grasp on reality the longer they’re alone? Watching Rings of Power feels a bit like that. You’re witnessing a story that’s not actually series of human interactions but a single block of inorganic text, ventriloquized by humans who seem less real with every minute that passes. After binging a few episodes, one’s sense of place and time begins to slip.

Last season’s writing inspired some conspiracy theories that the show had been written by, or at least used to develop, a proprietary AI.1 But I don’t think a language model, which by nature averages normal human speech patterns, could have accomplished something as mannerist and surreal as the dialogue from Rings of Power. (“We can crush two beetles with one boot.” “You’ve got some sand coming here.”) The writers seem to have misunderstood the fact that Tolkien’s style, while archaic, was always unpretentious: instead, they go for this faux-stately tone, generic fantasy NPC-speak raised to to a surreal kind of euphuism.2 Elsewhere, heavy-handed memberberries from the films and books (“some who die deserve life”) speak to a need to flatter fans, as will as a certain condescension — as though we’re supposed to be impressed when we hear famous needle drops from some of the most widely-known pop culture to ever exist. These referential moments land with underwhelming thuds amidst the otherwise transcendent weirdness.

At this point, the inexperience of Rings of Power's showrunners is as notorious as the show itself: Patrick McKay and J.D. Payne are first-time showrunners, but they are proteges and friends of J.J. Abrams, who put in a call with Amazon to make sure the project went to them. (More importantly, their former boss Lindsay Weber was a lead producer at Amazon and their pitch’s biggest advocate, a detail critics often miss in their focus on Abrams.) After a first-season PR campaign that feted them as wunderkinds, including a victory-lap cover feature for Hollywood Reporter, they’re lying low for S2. It’s easier to see why. Admitting that a Tolkien adaptation — which would normally be the pinnacle of a genre writer or showrunner’s career — was a “massive learning experience” and that they “didn’t know what [they] were getting into,” and volunteering that the S1E1 word salad was actually the concerted product of “hundreds” if not “thousands” of revisions, only revealed McKay/Payne as writers out of their depth and fueled internet frustrations even more.3 Anyone struggling to make a career, or even get stuff looked at, in the shrinking, gentrifying creative industries — actually, anyone who’s ever written a cohesive paragraph — has every right to be upset about the selection system that led to this.

Some people have positioned this show as a conflict between the “fake fans” writing the show and the “real fans” displeased with it. This is incorrect — Payne/McKay are real fans. They’re actually the most frustrating kind of real fans: Hollywood film nerds with industry clout and resources who approach things with the view that earnestness sets them apart, qualifies them to shepherd a project, and can supply them with the skills-equivalent of years spent doing on-the-ground work. If you listen to them on the Rings of Power podcast, it’s apparent that these guys were industrious, enthusiastic, and detail-oriented… about everything except confronting whether their writing was resonating as it should have been. They spent months and months in the production weeds: on the architectural strata of Númenor, on making sure the harfoots’ wagon wheels looked like circular hobbit doors, on discussing whether orcs preferred to be called “Uruks,” on building a working dwarf mine, and of course on inserting Payne into background art. McKay says that someone could write an analysis about how certain frames of the show reference classical paintings like Wreck of the Medusa or moments from Lawrence of Arabia. They stress their “references and cross-references,” but does any of that effort and complexity mean anything if the show’s basic foundations don’t work? If, comparatively, they plotted out the entire five-season-arc of a billion-dollar show in a “brainstorming session”? Ultimately, neither the richly-produced sets nor the symbolic interconnectedness nor the intricate philosophies of art mean anything when relegated to the background of a script that strains human believability at every turn.4

Anyway, the show. I’ve actually come to the conclusion that the version of Middle-earth depicted in Rings of Power is actually a Boschian hell dimension to which certain characters, who seem like they belong to the loftier Jackson/Tolkien universes, have been sent as some kind of punishment. These characters emit a certain maturity and presence that feels out-of-place; they stare with sunken eyes at the inanity around them, as if wondering: How did I get here?5 You feel like these particular characters could actually exist in a much better adaptation of the Second Age — as in, the show that people wanted this to be.

For those who haven’t seen it: Rings of Power takes place about five thousand years before the events of The Lord of the Rings, and depicts the backstories of several characters and nations. Elendil (father of Isildur, future founder of Gondor) has long been the show’s standout performance, thanks to the classically-trained Lloyd Owen. Elendil is family man and sea captain, bound by loyalty to the increasingly corrupt maritime power of Númenor. You can feel his weariness through every second of Owen’s performance: his mounting depression as his homeland spirals into demagoguery is palpable, as is his steadfast love for those around him even as they succumb to corruption. Elendil is allied to, and perhaps in love with, the deposed heir Tar-Míriel (Cynthia Addai-Robinson). Addai-Robinson has little to do this season, but her character — a headstrong girlboss in S1, now brought low by tragedy and blindness — has begun to radiate an eerie, mystic energy. Far be it from the writers of this show to actually elaborate on the “ways of the Faithful” or what this ancient religion means to Míriel, but Addai-Robinson is able to project its unspoken power through her haunted stare. We perceive that Míriel’s abjections have finally made her wise enough to rule, though we also sense that it’s too late for this Cassandra to save Númenor from its inevitable doom.

Back on the mainland, the dark elf known as Adar (played by Joseph Mawle in S1, and by Sam Hazeldine in S2) is perhaps the most intriguing and under-written character of the show. One of the elves twisted by Sauron to engineer the race of orcs, Adar — despite his obvious guilt and self-hatred — has chosen not to rejoin elf-kind but rather to lead and liberate his repulsive progeny. His emotional depths remain largely unexplored in any dialogue or plot development, but Mawle and Hazeldine find ways of communicating it physically: a growling voice, brooding Satanic stares. It helps that, under the leprous makeup, both actors are obscenely hot; Hazeldine in particular has incorporated a certain loucheness into Adar’s gait that sets him apart from the stiff, uncorrupted elves.6 He’s is a Cain-like figure, one of those rare characters that transcends bad writing through sheer force of personality. Even avowed haters of this show generally put respect on Adar’s name; one hopes for better material for him in the future.

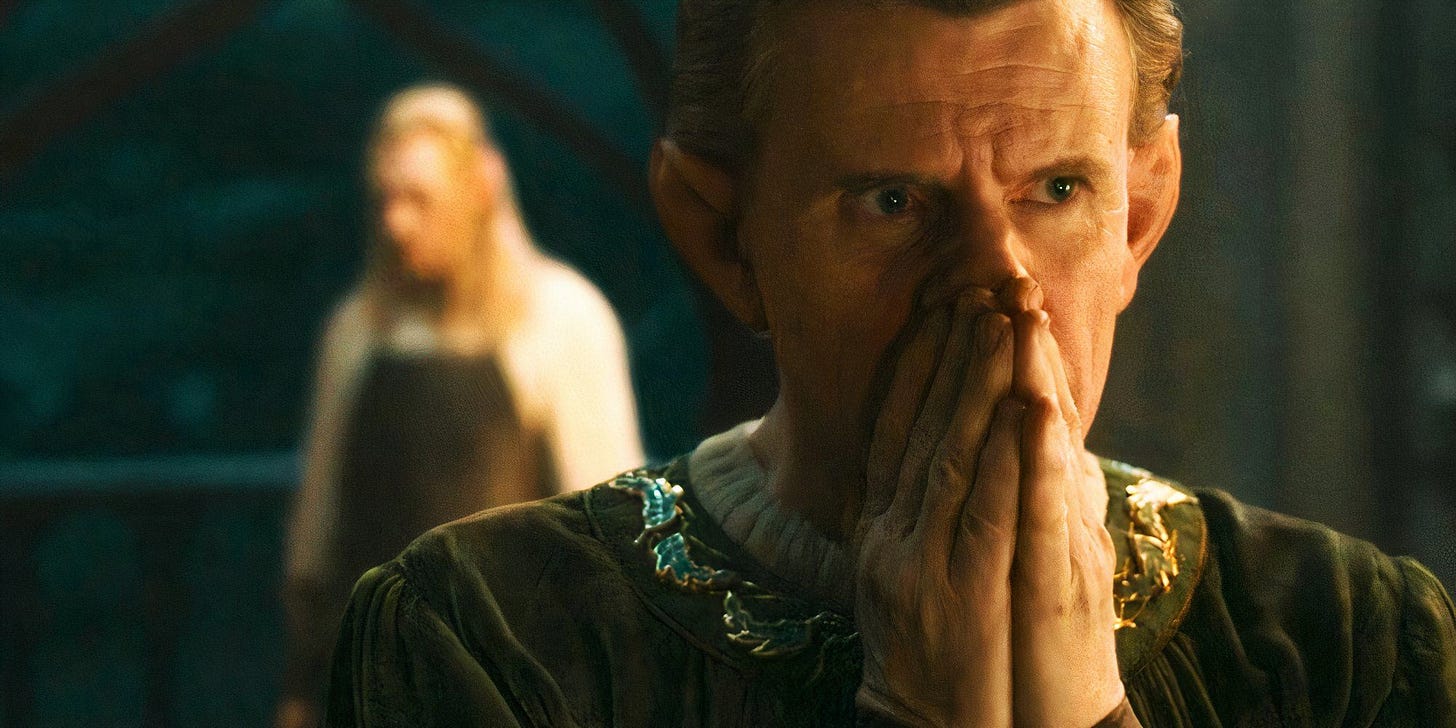

Otherwise, the core arc of this season is the fraught relationship between the elf smith/prince Celebrimbor (Charles Edwards) and the deceptive “Annatar,” the current guise of Sauron (Charlie Vickers). Taking the form of a “lord of gifts,” Sauron deceives Celebrimbor into forging the Rings of Power which the evil lord will later use to enslave the peoples of Middle-earth. The showrunners have taken a lot of shit for their portrayal of these two — specifically, for their deviations from Tolkien’s lore, in which Celebrimbor is a formidable ruler and craftsman, and the celestial Annatar is only able to mislead the elves into ring-forging through centuries of subtlety.

Rings of Power offers a small-scale, mundane version of these mythic events: Sauron/Annatar is a scruffy interloper in a series of bad wigs, and Celebrimbor is an easy target with no real backbone, somewhat middle-aged-looking for an elf. Sauron is permitted to enter Celebrimbor’s citadel after loitering outside for awhile; the two of them just kind of shuffle around and talk about whether they have enough mithril. An interesting essay on the subject by Mercury Natis makes the case that Payne and McKay reimagined the characters this way in order to preclude homoerotic tension. It makes sense: two obscenely beautiful young men in an obsessive, physically-involved creative partnership would probably have registered as gay for mainstream audiences. The essay is worth reading, though one thing I’d add (Natis’ essay predates S2) is that the Celebrimbor/Sauron relationship we eventually got, while not overtly homoerotic, does not feel particularly straight either. If anything, I’d call it camp and tragicomic in the Old Hollywood way. The elven smith’s relationship with Sauron feels reminiscent of All About Eve, or better yet Gods and Monsters:7 Celebrimbor as a greying, lonely, gay sophisticate who’s captivated by this rugged, young, helpful, probably-straight-but-maybe-not? stranger. (Charles Edwards has called him “besotted.”) They pass phallic-looking tools back and forth, and murmur personal confessions by the forge. Celebrimbor is never seen without one of his velvet Barry Manilow shirts. It’s a great time.

However, I doubt any of these dynamics are intentional on the part of the writers. The gentle campiness only works because of skillful acting by Vickers and Edwards, who together manage to salvage endless noneventful scenes of talking in the same room.8 Their talent is commendable — especially since the the most recent episode (S2E7, penned by showrunners Payne/McKay) seemed all but written to strip both characters of dignity.9 Overall, I’m highly interested to see how the writers close out their relationship in the season finale. Given Amazon’s desire to cut back on gore in Rings of Power (even when the directors try to go for it) I doubt this show will be able to depict the lore-accurate fate of Celebrimbor, one of the most gruesome sequences that Tolkien ever wrote. And if it did, I can’t see how such an end could approach the book version in tragedy or grandeur.

Notes on the other characters: not many. There’s precious little for any of them to do, and seem stuck in the same arcs as Season 1.10 The impetuous Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) is still feuding with the other elves, who won’t believe her when she says Sauron has returned, or is planning to do this or that. The harfoots and wizard are still roaming around in Rhûn. What keeps me going is stuff unrelated to the story:

Realizing that the elvish king Gil-Galad is played by Benjamin Walker of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson (why they cast this man in a role where all he does is stand and look censorious is baffling).11

Costumes by Luca Mosca are enjoyable, and lean heavily on the operatic and sumptuous. In particular, the Aegean-inspired Numenorean costumes incorporate marine textures like mother-of-pearl, and the beaded/embroidered robes of dwarf King Durin look splendid under candlelight. Some elements are overused (take a shot every time you see that economical gold foil on velvet), but overall this show is recommended for costume and fabric buffs. They even add little crystals to Galadriel’s chainmail (!!!)

Wig chaos. Some developments are good: Elrond gets longer, sexier hair, and someone noticed midseason that Annatar’s blond wig needed the split ends fixed. The harbor-lord Cirdan looks like Jimmy Buffett in E1, and then is shown shaving his beard (pointed ears on full display) in E2, as though production realized that only thus would audiences understand him to be an elf.12 Maybe they’re just dealing with time gaps, strikes, or reshoots.13 Additionally, they seem to have cowed to S1’s enormous fan outrage about the beardless female dwarves: this time, the dwarf women have peach-fuzz on their cheeks.

I’m also delighted to announce that the much-maligned “orc dad” has a name, and it’s Glûg (Robert Strange.) Glûg is delightful! I can confidently say that the online critics giving themselves aortal damage by complaining about Glûg’s existence are dimwits. The way they talk about Glûg, you’d think that he and his Orc Baby were part of some obnoxiously progressive, morally gray™ grandstanding against Tolkien’s (relatively) straightforward themes of good vs. evil.14 None of this is true. The Orc Baby appears for 2 seconds, and Glûg otherwise just hangs around and gnashes his teeth at whatever passes him by. What pathos he has is mostly due to his one-sided devotion to Adar — especially when he learns that Adar would gladly sacrifice the orcs’ lives for the abstract notion of orc freedom. This is as morally aware as Glûg ever gets, and it probably hurts his brain. Then he’s back to slouching around and dripping weird grease from his mouth as any good orc should.

Glûg, you’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.

Which brings me to another point: watching S2 of Rings of Power makes it clear that the vast culture-war controversy surrounding this show and its diversity/progressive “agenda” was pretty much just sound and fury. It’s obvious now that, despite some of the heartfelt convictions and backstories brought by individual actors,15 Rings of Power is not really interested in taking any stances socially or message-wise, or giving its actors of color meaningful, developed arcs. Much like the Star Wars sequels, its commitment to actors of color feels backtracked in the second installment. Take Arondir the elf warrior (Ismael Cruz Córdova), who was prominent in S1: this time, he’s in some episodes for less than 90 seconds, and sometimes not even that.16 I don’t think this pattern, which is true for several characters (many of whom have been killed off), was intentional on the part of the writers or showrunners; I assume (as with everything else) they’re simply oblivious to the fact that what they’ve written is uneven.

I really didn’t set out to write so much on Rings of Power, which is a low-hanging fruit that’s been criticized enough. I haven’t been personally invested in The Lord of the Rings fandom since high school, and have become really fond of the work done by the cast and crew. (Charles Edwards taught himself to forge rings! Charlie Vickers auditioned with Paradise Lost!) And on some giddy level, I consider myself blessed that in my lifetime, the most powerful company on Earth has funded what is effectively a multibillion-dollar production of “legolas” by laura with full authorization from the Tolkien estate.

I feel for the showrunners, who are good guys. But their approach just prompts a deep resistance in me, probably because I’ve worked for/ with so many corporate nerd types similar to them. Nerd writers often mistake “being able to talk about nerd things a lot” for “having a developed sense of what works in storytelling,” and it really shows. These days, the issue is corporate and cultural, as well as stylistic: if you’re a certain type of well-connected man the creative industries, “being able to talk about nerd things a lot” is often currency enough to be given a shot, or ten. During the time I was a script reader at an ill-fated film/comics company, I couldn’t count the number of rejections I was told to reconsider just because the writer was somebody’s friend, and because he was just so passionate about the genre he was writing in. Nor can I count the number of times I was made to add supernumerary beats or awkward bits of dialogue to treatments, just because they would remind people of Blade Runner or Inception or Lord of the Rings. I think that Rings of Power was able to came to fruition, and to garner such initial acclaim by critics, because Payne and McKay’s “brand” as creatives is really just to be exceptionally fluent in this high-geek sensibility. They can supply endless references to lore and enthusiasm for the IP that resonates with other nerds. During lead-up to S1, it was practically their only talking point: they were the biggest Tolkien guys out there. They cited passages verbatim. They greeted producers in Elvish. And these days, the most persistent section of the Internet still supporting Rings of Power is the geek-content industry, which can mine each episode for easter eggs and lore breakdowns and creature explanations.17

The biggest question about Rings of Power, which often poked itself over my shoulder like a admonitory skeleton, is: why care? Why treat this as a piece of cinema for which it’s appropriate to write extended complaints, when one can just (1) live and let live, or (2) shotgun its mind-bending writing and drift off into the dissociative planes of the So Bad It’s Good?

I suppose it’s half schadenfreude, and half frustration with the corporate calculus that uplifted this show over other projects, and earmarked a truly incomprehensible amount of money for it. Money that, in a time when so many filmmakers are struggling, could have gone to people who’d have made better entertainment (even kino) with it. The existence of this show actively prevented others, perhaps better ones, from being made. Ideas for Tolkien projects from more experienced creators were rejected, both by Amazon and the estate. Would they have been good? We will never know. Each episode of Rings of Power costs $58 million, and there will be 50 episodes — that’s the equivalent of 50 mid-budget movies. Actors and junior staff (many of whom have decades’ more experience than the showrunners) signed onto this project hoping it would provide a positive spotlight to their careers, and many have now been forced to contend with backlash. Rings of Power may give executives cold feet about other creators’ genre pitches in the future.

If this essay has a CTA, I suppose it’s to consider what you watch — especially if it’s good, especially if it excites or captivates you — and think about the systems of selection that allowed it to exist in such a form. What were the choices that determined what it would become? And, if you’re a creator yourself, how can you step back from your accustomed perspectives to make sure you’re making the right choices for your work?

How can we (unlike the dwarves) dig upward?

Season finale update 10/3: they killed Adar and Glûg. Arondir got one (1) line of dialogue.

And do check out the footnotes! They’re probably half the essay this time.

Mercury Natis: “Rings of Power’s Celebrimbor Problem”

Thom James Carter: “Middle-earth Crisis: On a lack of zaddies”

Gods and Monsters (1998)

Jimmy Buffet, “Cheeseburger in Paradise”

Most scenes in Rings of Power share that eloquent-but-plotless style that characterizes AI creative writing, especially when you ask the AI to mimic a scene from fantasy fiction (e.g. characters will say ridiculous “draw thy swords!” dialogue back and forth, and then the scene suddenly ends).

Showrunner J.D. Payne says: “I’ve also spent a lot of time studying Hebrew poetry and parallelism and inverted parallelism and chiasmus and all these cool rhetorical strategies that poets and prophets from thousands of years ago would use to communicate sacred material….Some of [the characters] will speak in dactyls. Some of them will speak in trochees.”

Now that S2 is almost over, it’s apparent how dramatically the winds have turned for Rings of Power. Media outlets, after dutifully clapping for S1, have largely declared open season on the show. Viewership numbers indicate collapsing interest, and I feel like many of the chill fans they were banking on to tolerate this show, or at least not badmouth it, have simply walked away. I mean, this season’s trailer dropped Tom Bombadil — something I’m confident would have broken the Internet five years ago under a better-managed franchise — to barely an online ripple. (The show, predictably, does nothing with Tom Bombadil.)

Rings of Power actually reminds me of another (slightly less bad) auteur work: The Northman. Not only for the big-budget fantasy epic aspect, but the impression that these vast production worlds were created not as entertainment for audiences but as mind-palaces for their directors/showrunners. I recommend this New Yorker article on The Northman, because in retrospect you can see a lot of the mentality behind the movie: so much effort was spent on getting every little period detail right, but the film itself (imho) suffered from perhaps the cheapest problem to fix but the most difficult for a creator to acknowledge: inaccessible writing.

And you may find yourself living in a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell; And you may find yourself living in a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat. And you may ask yourself, “My god! What have I done?”

All of this is just to say that if Adar had gently handcuffed me to that chair as he does Galadriel in S2E6, I would not have had Galadriel’s composure.

I’m sorry Gods and Monsters written and directed by Bill Condon you do not deserve to have your academy award winning screenplay be compared to Rings of Power

There’s a brief sequence when Sauron steps into the fire to change forms from Halbrand to Annatar that’s pretty cool visually, and you finally think things are kicking up a notch, but then they just go back to nonstop talking per usual, except Sauron has an Aryan wig now

how it feels to microwave pad thai at 3 am

In a sidequest a la Gaslight (again, this Celebrimbor is an Old Hollywood gay!), the elven smith realizes that he’s been trapped in a peaceful illusion by Sauron so that he will keep forging rings while the city of Eregion falls around him. He comes to this conclusion when he realizes that a certain mouse is regularly making the same rounds of the floor like a screensaver; plus, the candles aren’t burning down. When he leaves the tower and tries to tell people that Sauron has ensorcelled him into making the rings, no one believes him, even though they were all suspicious of “Annatar” mere days ago. Celebrimbor says, “Look! his blood is black!” and then Sauron holds up his hand and his blood is red! Foiled! Sauron/Annatar then uses magic to make Celebimbor’s arm bitch-slap his assistant Mirdania off the battlements, where she lands in the mud and is disemboweled by orcs as the elves (who are right there with bows in hand) just kind of watch. Sauron locks Celebrimbor back in the tower in handcuffs. Despite being a literal metalsmith with access to forging tools, picks, etc, (we see Galadriel pick her handcuffs easily in the same episode) Celebrimbor decides to amputate his own thumb with a crimper. Personally I think Charles Edwards deserves a Purple Heart for this episode alone.

Was the looping mouse from S2E7 (see footnote above) actually a cry for help?

Shouldn’t he have played Tom Bombadil? Hmmmm?

An earlier version of this review said “as if production only then realized that he was supposed to be an elf.” But actually, the bearded representation of Cirdan is the Tolkien-accurate one.

This is even more interesting to me. To have Cirdan change his look so suddenly after only one episode makes me wonder just quickly after filming these episodes are being focus-grouped. Did an audience get confused? Why decide to have him shave instead of simply displaying the ears?

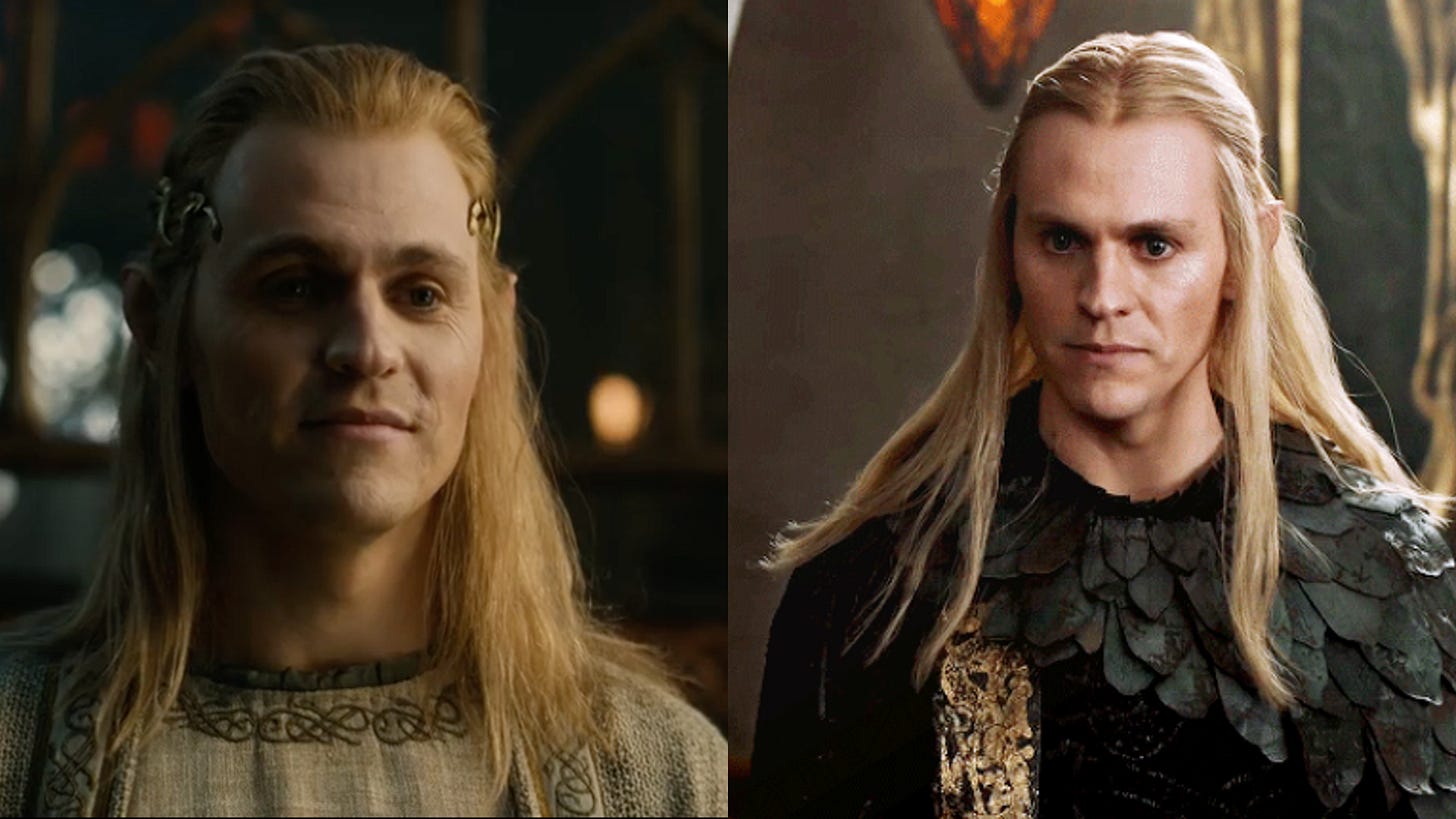

Wig history:

Side note: Elrond was originally supposed to be played by Will Poulter

They really need to solve the forehead problem of their elf wig styling, but the second one is so much better

First of all, it’s clear from anything Tolkien wrote in letters/own takes that while “good” vs “evil” might have been the broad overarching categories, his species and cultures were often very complex in their flaws, roles, attitudes, and manifestations of said categories.

Also, if you listen to McKay and Payne in podcasts, it’s clear that they’re just as devoted to honoring Tolkien’s clear dichotomy of good and evil as many of the traditionalist fans who criticize them. In fact, they go on and on about it. I recommend this episode of House of R if you want to hear them talk at length about Middle-earth’s moral structure. There’s also the fact — which provides an interesting gloss on the show — that Payne is a devout Mormon and speaks very movingly about his spirituality. But overall, the allegations that the two of them are out to take down the moral order of Tolkien’s works is very wrong and actually concerningly stupid.

I highly recommend Ismael Cruz Córdova’s wholesome interview where he talks about his childhood aspirations to be an elf, as a kid from the mountains of Puerto Rico whose best friend was a mango tree. This man deserves the world

In S2E7, they also cut huge parts of a fight scene that Córdova rechoreographed himself to make it accurate to his character.

Speaking of creatures, Rings of Power desperately needs its own Gollum or Glup Shitto. There are no funky little guys running around this time doing weird little voices. For shame.

I run in Tolkien spaces where you constantly have to hedge if you don't want to be lambasted by hyperdefensive fans of the show on the one hand or dogpiled by the worst people on earth on the other, so this is very cathartic. It's clear Payne and McKay are big Tolkien fans, but they are also terrible storytellers who failed upward into a billion-dollar deal, sticking some very talented people with the most dogshit material imaginable in the process. (I knew about J.J. Abrams but not about the Lindsay Weber connection, thanks for that.) I wrote about this when S1 finished up, but the whole enterprise feels like a Ring of Power itself: an attempt by powerful forces to artificially extend the good feelings you get from reading the books or watching the Jackson films, but it only grows more tired and withered the longer it stretches on. Butter scraped over too much bread. Thank you for summing up my frustrations!

I think you hit the nail on the head here re: what qualified these guys to write a Tolkien show? Tolkien was a complicated thinker. He was not right about everything and he was serially frustrated by people who wanted to deify his work. He hated most things and especially the fandom that was already growing up around LOTR in his own lifetime. He would have hated this show.

But more deeply than that, there's a deep divide between story-lore that is meant to say "The world is always changing and losing something of what it used to be and attempts to resist that are doomed to fail and even to bring lasting misery to the world," on the one hand, and two dudes saying "Hey, remember how great The Lord of the Rings movies were? What if we had a TV show based on that and felt some of the magic again?" on the other.