FIVE FATES: Sci-Fi's Nightmare Blunt Rotation

That time Harlan Ellison, Frank Herbert, and Poul Anderson teamed up for one strange, terrifying project

I’m in a weird place professionally. To get a job in publishing, it’s pretty much imperative that you stay abreast of recent trends and read voraciously from current frontlist books. And I certainly try. But left to my own devices, I inevitably end up crawling back to New Wave sci-fi like a starving flatworm whose only brain cell yearns for stream-of-consciousness novellas about interdimensional alien sex written fifty years ago by chainsmokers in dagger-collared shirts.

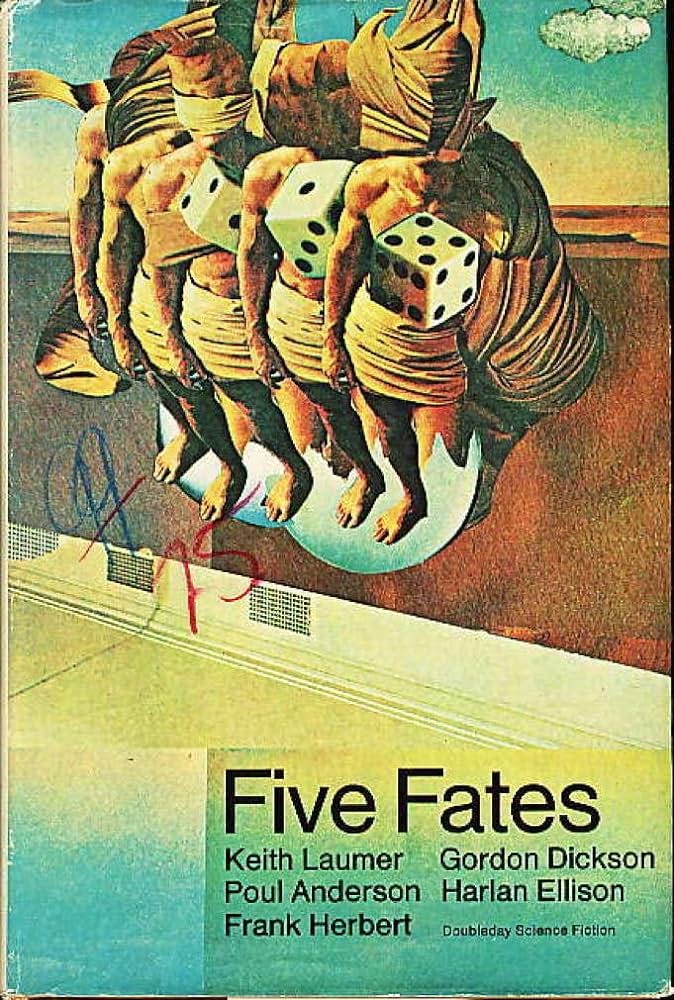

If you share my foibles, or if you’re simply in a reading rut, you’d be hard-pressed to find something more exciting than Five Fates. Not only does it boast a sci-fi supergroup (Frank Herbert, Harlan Ellison, Poul Anderson, Gordon Dickson, and Keith Laumer), it provides a fascinating snapshot of where speculative fiction was “at” during a pivotal moment of the genre’s history.

The New Wave of speculative fiction, which roughly spanned the 60s through the 70s, was a period of wild collapse and re-expansion: bizarre, innovative prose; nonlinear plots; deconstructions of gender, race, and social mores; universes that splintered into multiverses and converged again. Science fiction’s previous era, known broadly as the Golden Age, had consisted (generally) of fictional worlds that aimed to feel solid, real; contrastingly, the New Wave’s project was to interrogate, or even shatter, this agreed-upon notion of reality. For me, the best analogy for what the New Wave did (still does) for readers is that scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark: glowing wind escaping the forbidden box, revealing beauty, mystery, and horror equally.

Five Fates, published in 1970, positions itself firmly in this mindfuck vein of the New Wave. Per the jacket copy, it’s “one of the most bizarre and original fictional concepts ever created,” a showcase opportunity for five of spec fic’s foremost writers to go absolutely wild. Its biggest names are red-hot at the time of publication: Frank Herbert has just finished Dune Messiah, and Harlan Ellison is in the midst of his decade-long, nearly-unbroken Hugo streak (he’s hard at work, the back cover informs us, on Again, Dangerous Visions.)

The central concept of Five Fates is this: all five contributors were sent the same disturbing prompt — in some dystopic world, a man named William Bailey is admitted to a Euthanasia Center and killed. The surrounding questions — how did he get there? how did society descend to this point? is there an afterlife? — are left up to the writers to flesh out. Each of the five resulting novelettes (which average around 30 pages) offers a vastly different concept, style, and literary goal. It’s a literary blunt rotation/samsara, a hallucinogenic journey that produces several great tales and one masterpiece.

Honestly, the less you know going into the book, the better. I’d even recommend skipping the jacket copy and going in completely blind; the thrill of discovering what each writer has done with the prompt is worth it. The reviews below will contain little or no plot information.

1. Poul Anderson, “The Fatal Fulfillment”

Verdict: pretty good at points

Anderson was an extremely idiosyncratic talent, a fantasy and sci-fi writer from the Golden Age who was able weather the transition to New Wave with some success. He’s most well-known these days for The Broken Sword (a Norse fantasy that heavily inspired Moorcock’s Elric works). Anderson was a remarkable prose stylist, and can pretty much crank up the eloquence to 11 at will. In “Fatal Fulfillment,” he does so right out of the gate, with one of the strongest opening paragraphs of the book.

Death was a stormwind. It was as if he were blown, whirled, cast up and down and up again, in a howl and a whistle and a noise of monstrous gallopings.

Hindering the story are long, uncreative jabs at the usual late-sixties punchlines (hippies, coddling therapists, quarrelsome liberation groups, “Berkeley”) that never amount to anything thought-provoking, and can often feel cruel and over-indulgent. But working in the story’s favor is a pretty innovative central concept, and some really gorgeous writing. I was a weeping mess within one page (spoiler in the footnote)1; overall, the story is worth reading and thinking on.

2. Frank Herbert, “Murder Will In”

Verdict: oh hell yeah

Herbert’s relationship to the New Wave is interesting — he frequently referred to himself as somewhat separate and independent, with different objectives. Reading the Dune books, I’ve become fascinated in particular with his writing style, which constitutes a kind of anti-eloquence: difficult, often jarring prose that focuses on conveying foreign cognitive systems. Herbert, who was quite capable of writing with a natural-sounding flow or mellifluousness when he wanted to, usually opts instead for alien jargon — the better for communicating novel ways of thinking and existing.

As soon as you gain a foothold on the story’s mechanics, “Murder” is a fascinating journey of body-hopping, cruelty, and survival. Classic Herbertian themes of bureaucracy, social control, abuse of power, and mental conditioning are present at every turn. Its sheer strangeness and intricacy hammer home the fact that Herbert’s creative mind really just had “5D chess” as its default setting. Highly recommended for anyone interested in his work outside of Dune.

3. Gordon R. Dickson, “Maverick”

Verdict: oof

While many authors during the New Wave period were penning innovative and pathbreaking works, it should be noted that many others were just continuing to write entertaining stories set in Flash Gordon-y worlds that were mildly original at best. “Maverick” is one of these, a decidedly normcore tale told by a competent writer; it would be less underwhelming if it weren’t in such genius company.

Dickson explores a sci-fi concept — having your consciousness projected into a non-human creature in a parallel universe — that also occurs in his Dragon Knight books. However, the philosophical problems and phenomenological shocks of such a translation (e.g. all those classic Avatar questions of selfhood, or ruminations on what it would be like to have a new body and brain) are largely sidestepped for standard, plot-first storytelling. In a story in which plenty of wild directions might be taken, Dickson is most comfortable with conventional earthling plot beats (a courtroom showdown??) and formulaic, all-American heroism (see: the title). Action takes precedence over theme: our hero has to fight the guy, escape the place, etc. If you’ve ever thought to yourself, “I wish H.P. Lovecraft’s Shadow Out of Time had been written by Brandon Sanderson instead,” this might be the story for you.

4. Harlan Ellison, “The Region Between”

Verdict: Masterpiece

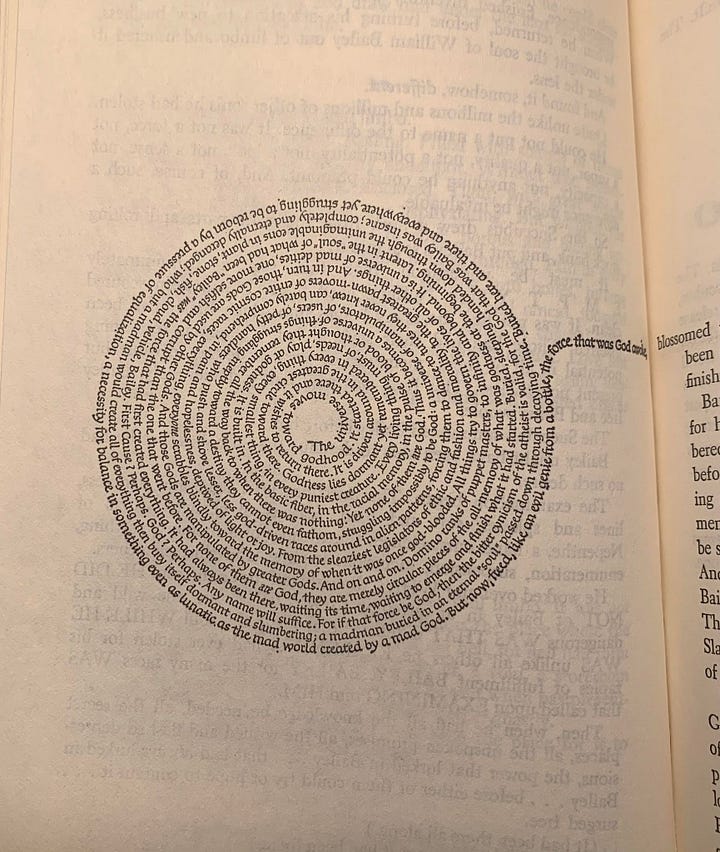

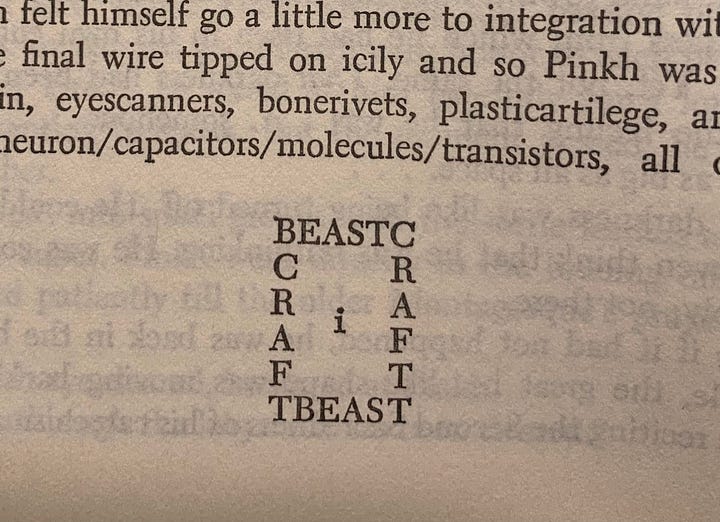

I feel vaguely bad giving another win to Ellison; if speculative fiction in the 70s had been a Little League, some kind of slaughter rule would have been invoked based on how well he wrote, how frequently he won awards, and all the ways he came to dominate the field as a public figure. “The Region Between” (which can also be found in Ellison’s later collection Angry Candy) is another showstopper of his, unforgettable and original. This story, like much of Ellison’s work, is an attempt to deconstruct not only the conventions of speculative fiction but those of the short story/novella as a whole.

If you’ll allow a brief digression, there’s a conversation between Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan that lives rent-free in my mind. According to Cohen, the two have been comparing skills as songwriters when Cohen says, “You’re Number 1; I’m Number 2.” Dylan replies, dryly, “Leonard, you’re Number 1. I’m Number Zero.” Anyway, stories like “The Region Between” make it clear that Harlan Ellison, at this stage of his career, was operating in Number Zero territory. The story’s scope is vast and metaphysical, and it puts the cleverest spins on the prompt components. It’s got the most lively (but vulnerable) protagonist, and the most powerful, intriguing antagonist. It plays formalistically with typesetting and symbols. And it’s funny — funny! Damn him! Damn that man to hell!

5. Keith Laumer, “Of Death What Dreams”

Verdict: kind of a mess

This is sadly not a very good story. The same kind of classic American hero that featured in “Maverick” features in this one, and is extra maverick-y. Everyone around him underestimates him, and everyone is wrong (until they’re grateful). There’s no high-stakes situation he can’t charm his way out of, no supporting character he can’t inspire to think bigger.

“I owe you... You shook this whole lousy setup to bedrock, something that needed doing for a long time.” […]

“I’ll go alone, Gus. Just give me the name and address, and I’m on my way.”

“You don’t waste much time, do you, kid?”

“I don’t have much time to waste.”

Oy.

From a historical perspective, “Of Death” is interesting mostly because it belongs to a certain subtype of science fiction that could be called Taxipunk: dystopian, crime-ridden futures strongly rooted in the crumbling, vice-ridden cities of the 70s. Central tropes include criminals, lowlifes, corruption, overpopulation, urban decay, and obviously taxis. (Other examples include the “Harry Canyon” sequence in Heavy Metal, Soylent Green, anything by Ralph Bakshi, and Dhalgren at points.)

But these elements never pay off; instead, Laumer opts for an ending completely out of left field, at which point all our hero’s previous hustling ceases to matter. Which is a shame; a gritty, workmanlike story wouldn’t have been a terrible way to close out the collection, but instead we’re treated to a sudden (and nearly literal) deus ex machina that feels like a panicked effort to rise to the cosmic scale of the other entries. It’s too little, too late, and feels inauthentic.

And that’s the book! Overall, the format of five novelettes was great: the stories were just long enough for serious immersion, and just short enough to keep excitement high. It honestly seems an ideal format for today; short works are back in style, and I can think of several circles of horror and speculative writers that would make for interesting, event-worthy collections. (Drop your ideal blunt rotations in the comments.)

I was, for unrelated reasons, thinking about the "Machine of Death" duology from ~a decade ago (in which you had ~30 writers all writing short stories with the premise "what if a machine at CVS could take your blood sample and give you a one-word description of your cause of death"), and I think as I try to remember the premises of the individual stories, a trend emerges. The first book, IIRC, was mostly jokey Asimovian AS YOU KNOW twist ending pieces (which are fun! I love Asimovian AS YOU KNOW twist ending pieces!) with the exception of one piece called, um, "Miscarriage" (skull emoji), but with the second book, having exhausted all that stuff early on meant that (again, IIRC) you started getting really abstract high-concept stuff. (I distinctly remember a story that between 216 seconds, minutes, hours, weeks, etc into a girl's life.) Fun seeing people, many of them amateur fiction writers, go from Golden Age to New Wave in, like, two years.

Again - only tangentially related to this very cool seeming book! I am laughing at that concrete poetry in the Ellison excerpt. I really should get into some of his stuff!!