Fourth Wing Review: Starship Troopers (for Girls!)

Military grimdark, eroticized violence, and publishing's quest for the next female power fantasy

In 1958, Robert A. Heinlein wrote a novel at breakneck speed and fired it off to his publisher. He was spurred by outrage — the US was about to suspend its nuclear testing program, leaving itself vulnerable to the Soviets; the country had, in Heinlein’s estimation, become “washed up.” Written as a warning, Starship Troopers was darker in tone than Heinlein’s previous YA space-adventure novels. It depicts a grim, militaristic future in which humankind is locked in a battle for survival with aliens called Bugs; it follows a kid named Juan “Johnnie” Rico as he rejects his bourgeois, peacenik family and transforms into a soldier for the planetary state.

Heinlein’s editor rejected Starship Troopers immediately, prompting furious back-and-forth about its suitability for kids and eventually a twenty-page objection from Heinlein, who believed that the nation’s “youngsters” were ready for hard-hitting ideas and more bracing content. He sent the manuscript to The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, where it was serialized in 1959; a novel edition came later that year.1 Initial reviews were confused about its intended audience (was it for kids? adults?) and critical of its didactic passages about the military and moral philosophy: the San Francisco Chronicle called it a hymn to Heinlein’s personal “cult of violence,” and Kirkus deemed it a “justification for the moral validity of war [and a] menacing sort of ‘brainwashing’” for teen readers.2

Criticisms of Starship Troopers’ themes, while hyperbolic, were not entirely off-base. In Heinlein’s world, the ideal military life is violent, abusive, and deindividualizing; death is and should be omnipresent at every stage of training. For example, there’s the basic training exercise in which

… they dumped me down raw naked in a primitive area of the Canadian Rockies and I had to make my way forty miles through mountains. I made it [by killing rabbits and smearing fat and dirt on his body] … The others made it, too… all except two boys who died trying. Then we all went back into the mountains and spent thirteen days finding them…. We buried them with full honors to the strains of “This Land Is Ours”… They weren’t the first to die in training; they weren’t the last.

Through the eyes of Johnnie, we experience an intensity of life that makes civilian existence seem anemic, even pathetic. We fight cheek-by-jowl with his tight-knit platoon, the Roughnecks, all “physically perfect, mentally alert, trained, disciplined, blooded”; we sleep in naked groups to stave off hypothermia. We follow them through battles with 80% casualty rates; we witness executions, whippings, nuclear firestorms. The ultimate genius of Starship Troopers is how it combines steely first-person narration, thrilling action sets, and a sense of raw, survivalist libido to infuse the concept of sci-fi “soldierhood” with heightened power and attraction.

In a retrospective essay “Starship Stormtroopers” (not without its own flaws), Michael Moorcock describes how a reader needn’t be a war hawk to become entranced by Heinlein’s world. “A stirring image is a stirring image,” he points out, and fictional depictions of blood, destruction, and death “can be employed to raise all sorts of atavistic or infantile emotions in us.” Moorcock contends that this sensationalism flourishes particularly in sci-fi and fantasy, in which the end goal of “escapism” can justify vast body counts and grandiose scales of fictionalized war. Leftists, rightists, tame centrists — we all seek it out. And Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, despite persistent criticism and the famous 1997 satire film by Paul Verhoeven, remains a popular, acknowledged classic to this day.

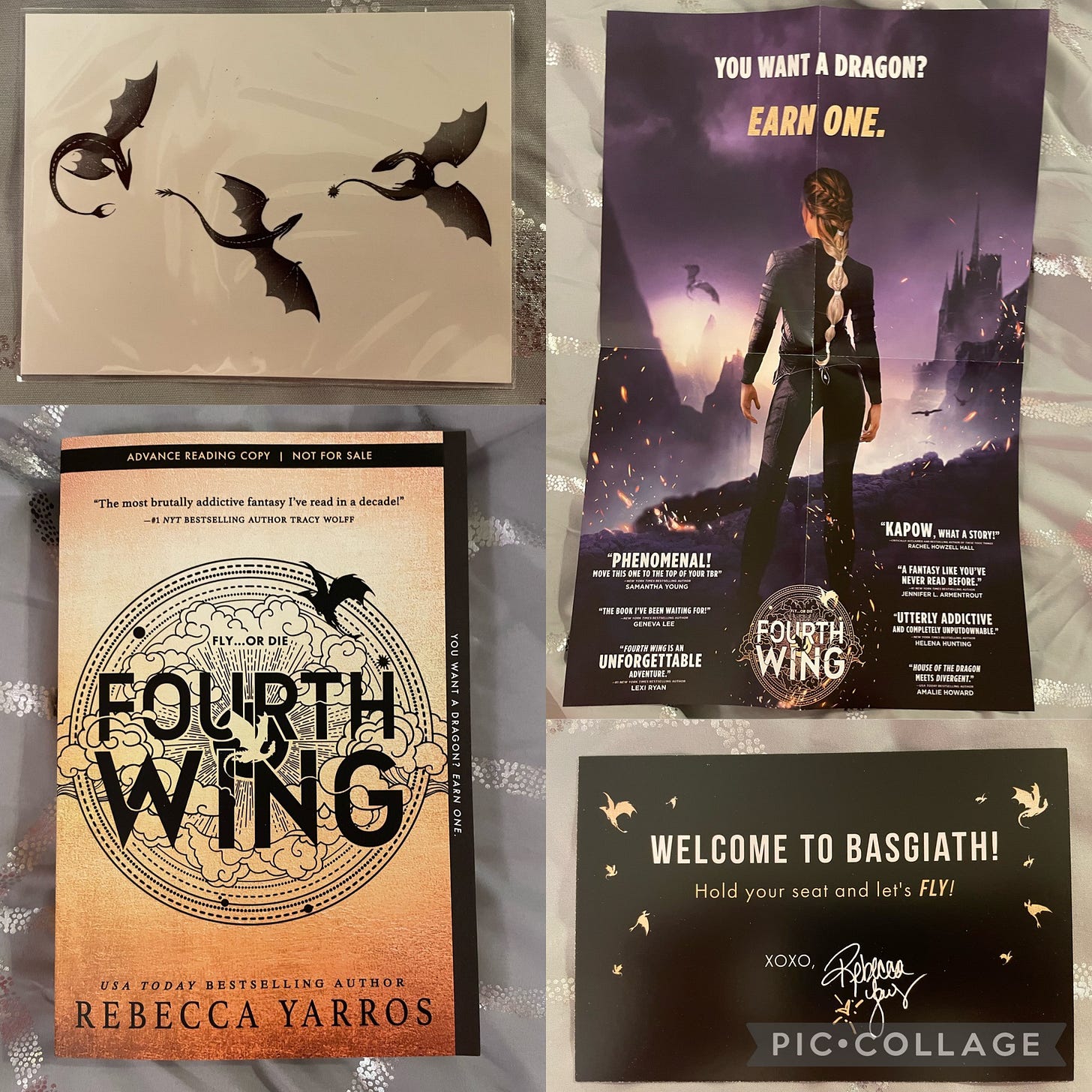

With all that being said, it feels wrong to mention Fourth Wing in the same breath as Starship Troopers. Putting aside the fact that Fourth Wing is a poorly-written work whose prose has been critiqued to death by many people before me, the two books seem to represent opposing moments in publishing history. Heinlein, for all his faults, was writing “up” for an audience of teens, treating them as adults and including them in the sphere of “adult” science fiction, with complex worldbuilding and (relatively) sophisticated themes. Sixty years later, Fourth Wing and its team (author Rebecca Yarros and Entangled Publishing) represent a publishing world moving in the opposite direction: creating books for adults in an actively juvenile style, and cultivating an audience of adult readers who no longer demand that published books have good writing at all so long as they check necessary boxes of sensation and eroticism.

But thematically and content-wise, the two books are as close as one could possibly get. Fourth Wing, like Starship Troopers, sells a military coming-of-age story in which mass death is a part of the allure (“brutally addictive,” says the cover blurb). Someone on Reddit puts the death count of Fourth Wing at 222 cadets, plus an untold number of civilians — though it’s widely considered a “fluff” read. Its primary audience (and the primary audience of most mainstream fantasy now) is female, young, progressive, and would probably be aghast at being compared to grimdark bros, Heinlein apologists, or men in general. And yet here we all are, hooked on the same stuff.

Fourth Wing tells the story of Violet, a sickly girl with purple eyes and naturally ombre hair from the country of Navarre (not the one in Spain — fuck if I know). Violet is forced into the deadly Basgiath War College, where students endure grueling combat training and are bonded to magical dragons. These rider-dragon pairs serve in Navarre’s war with the neighboring country where people ride gryphons, because this is also the fantasy novel I wrote when I was 12.

Yarros’ worldbuilding, and the eagerness with which she disposes of faceless extras, is Heinlein-style grimdark on an industrial scale. The College’s entrance exam, which consists of climbing a tower and crossing a narrow parapet, kills “roughly 15% of the rider candidates.” Within the war school itself, we’re told that half the candidates die in the first year, another third in the second, and a final third die in the last. Another 10% die in their final “War Games,” for total fatality rate of 80% over three years. Trainees are encouraged to kill each other and weed out the “weak links,” and the dragons incinerate unworthy students who show any sign of fear. Extreme!

As a rider, Violet gains access to the kind of adrenaline highs, magical gifts, high-octane sex, and physical prowess that civilians can only dream of. In the world of Navarre, the elite riders serve as bearers of the universe’s stark, uncomfortable truths, waited on with trembling hands by the effete scribes and healers, who (we can assume) don’t know how coddled and lucky they are in their sheltered ivory towers. Like the cadets in Starship Troopers, the riders attend frequent ceremonies that reinforce their privileged status as witnesses of death: teachers give daily readings of the “death rolls” at assemblies, and stiff-lipped military funerals (in which bodies are cremated in an oil drum) provide Violet with moments of “sobering” truth about how death is everywhere and that she needs to be even tougher to survive. She won’t be the next statistic — she’s a survivor.

Like Starship Troopers, Fourth Wing disguises its deep enthusiasm for death with an affected tone of soldierly gruffness, the kind that you’d expect from any “realistic” war film in which grizzled seniors spout lines like “war is hell, kid” to their wide-eyed, greener charges. In Fourth Wing, most of these lines come from Violet’s crush, the square-jawed Xaden, who’s positioned as the kind of guy who tells it like it is. As happens in most military fantasies, “telling it like it is” often looks a lot like an unquestioning veneration of death, barely disguised beneath posturings of cynicism and tough love. When a fresh recruit asks Xaden for some advice and encouragement, Xaden eviscerates his neediness in front of his peers:

You’re not going to make it… If [you] need a fucking pep talk, then we both know [you’re] not [making it] out of the quadrant on graduation day. Let’s get real. I can hold their hands and make them a bunch of bullshit empty promises about everyone making it through… [But] in war, people die. It’s not glorious like the bards sing about, either… It’s hard, cold, uncaring reality… So if you won’t get your shit together and fight to live, then no. You’re not going to make it.

And, later, when someone suggests that nonviolence is an option:

Stop. Fucking. Coddling… You never get used to killing, but you do understand that it’s necessary. This isn’t primary school. This is war… [and] the ugly truth that those not on the front lines choose to forget is that there are always body bags in war.

Nothing personnel, kid. Xaden is fond of such declarations, and Yarros has him make them regularly. You get the sense that each of Xaden’s speeches is supposed to land as a truth bomb, have an awestruck female reader breathless at the sheer danger of Real Military Life and the psychological hardening it requires of soldiers. Imagine a book in which every speech is “You Can’t Handle The Truth,” except Jack Nicholson is actually in the right, and also we’re supposed to want to fuck him.

It’s worth delving into Xaden in particular, since he’s arguably the most important part of the book, the eroticized avatar of its no-nonsense military aesthetics and abstracted violence. If Heinlein (himself a former soldier ex-military)3 crafted Johnnie Rico as a way for young men to imagine themselves in the armed forces, Yarros (an Army wife, who makes no secrets of how her husband inspires her “book boyfriends”) has created Xaden as a way for female readers to imagine themselves romancing the Soldier.4 “Every edge of Xaden’s body,” Violet observes, is “honed like a weapon, all sharp lines and barely-leashed power.” His most sexually-charged interactions with Violet take place on the combat mats; daggers caress throats frequently. When he removes his shirt, we see his 107 ceremonial scars: these represent the 107 soldiers’ lives under his care, for whom he suffers and grits his teeth each day. Violet caresses these.5

Xaden makes it his mission to train Violet into a real Soldier like himself, and much of the erotic momentum in Fourth Wing is how Violet comes to embody the thing she desires. By the end of her training, Violet has effectively become Xaden; her body mirrors his, with a bandolier of daggers, similar tattoos, and hardened muscles. Via their telepathic link, she can experience the sex they have as Xaden, including her own penetration. She is rechristened “Violence,” and comes to believe that her experience dealing with chronic pain gives her a superior edge over other people. (“I’m used to functioning in pain, asshole,” she gloats at a wounded enemy. “Are you?”) She comes to prefer Xaden’s badass friend group to hers, who “baby” and “take it easy” on her.

All of this is framed as self-actualization, as Violet realizing her own power. She learns to thrive in the harsh environment around her, immured to mounting casualties and capable of ever-increasing damage. “I’m a fucking weapon,” she proclaims, orgasmically, when she discovers she can kill with lightning, and is now one of the most valuable assets of the war.

Over the past 10 years, the world of women’s fantasy has changed dramatically. Sometime after 2016, when millions of people watched Daenerys Targaryen walk messianically out of a fire as her rivals burned to death, publishers began to slowly take note of how women, by and large, were not as antipathic to the violent lures of grimdark elements as they’d thought. As a demographic, they just needed proper courting: feminist talking points (“female rage”), tasteful covers (graceful text, no more muscly sword guys), and marketing campaigns that focused on the platforms women used (Instagram, YouTube, and recently TikTok). From there, you can sell female readers the same shock value and replicable gore that have hooked male readers since the early days of Conan. In recent books, we see Nietzschean heroines inflicting carnage on a mass scale: slaughtering their families, burning kingdoms in their wakes, immolating enemies, etc. Titles, as a meme, increasingly revolve around “burning,” “war,” “ruin,” “wrath,” and “fire.” Women’s fantasy has essentially become Starship Troopers: a thriving forum for the same kind of violent power fantasies that got Heinlein shadowbanned from mainstream sci-fi, or for which Zach Snyder and whole D.C. aesthetic became critical punching bags.

Fourth Wing is the natural evolution of all these trends, and Rebecca Yarros’ military preoccupations just happened to fit perfectly into the wider demands for darker, battle-hardened content. What’s more, Fourth Wing happened to hit shelves just as the fantasy genre, via the romantasy boom, experienced one of its periodic expansions into new audiences. Newcomers to the genre looked at its astronomical death rates and fusion of violence and sexuality, and they were honestly impressed. As one blurber proclaimed, it’s fantasy “like you’ve never read before.” A stirring image is a stirring image.

Do actually I think that, after reading Fourth Wing or the like, female readers will be drawn towards real wars or military ideologies? Obviously not, just as D.C. fans and Snyder bros never turned into the violent hordes that critics feared, and Starship Troopers never actually converted any sci-fi nerds to fascism. Some books are just pretend, with themes and settings serving as a cover for more lowly drives: spiking adrenaline, getting you off, making you turn the next page.

The readers, writers, and publishing staff that propel these violent books do so because they deeply need that adrenaline and escapism. American women come home from isolating, uneventful jobs, face an eroding economic landscape and disintegrating healthcare, jump through ever-increasing educational hoops for jobs that will pay less when we finally get them, and have our brains sandblasted every hour by the Internet. Women, like men, face unprecedented levels of loneliness; our ideas of other people are becoming distant and derealized. Of course these books — with their brutal hellscapes, melee battles, and blood-spattered muscles — appeal right now. Grimdark destruction feels more vivid, more cathartic, and more grand than whatever exhausted fugue has taken hold of our real lives. The genocidal death counts and “who hurt you” neck-snapping in modern women’s fantasy are a replicable, commercial way for publishers and authors to escalate the stakes, deliver hits of stimuli, and give the impression of purpose, struggle, meaning. And that’s exactly what’s so cynical and ultimately dumb about it. Violet is a fucking weapon — we just watch. And we grow more detached from real life, including actual war and violence, by the day.

I don’t know where these things are headed, or when this trend will peter out. I can say with confidence, from skimming through the trades, that copycat manuscripts are being gobbled up by publishers, and infrastructures are being set up by the Big Five to produce another Fourth Wing. That, at least, is the financial side.

On the social and literary side: I joined a writers’ Discord server recently. The fantasy writers — primarily women — had been discussing their extravagant ideas for killing off characters so intensely that a whole separate channel had to be arranged for it.

“I don’t know what to do with the side characters,” said one writer, in the main channel.

“Kill them,” offered another.

“Just because I don’t like them?”

“It’ll be fun,” said the reply. “You’ll like them much better dead.”

The serialized novel was called Starship Soldier. Other potential titles included, unironically, Dulce et Decorum.

Curtis A. Weyant’s excellent piece on the publication history of the novel reveals that Kirkus (in a funny bit of pre-Verhoeven foreshadowing) actually checked with Heinlein’s publisher, Putnam, to make sure Starship Troopers wasn’t actually satire.

In the Herald Tribune, Anthony Boucher (founder of F&SF, writing under a pseudonym) declared it an “irate sermon with a few fictional trappings,” though he noted that the F&F serial was better. The essay “Heinlein Criticism and the Scribner's Juveniles” has the reviews from Kirkus and The San Francisco Chronicle.

Corrected! Thanks to Kirk in the comments.

Yarros’ views about the military are best described as complex. She wrote an open letter (now stricken from the Internet) in 2019 denouncing the never-ending wars for which her husband was constantly deployed, citing the crushing burdens it placed on her family, including her sons bickering over who got to be “man of the house.” At the same time, she’s also informed critics of the war in Afghanistan that the first amendment is “a constant, never-ending purchase that's paid for with the blood of the US Military” and that actually, civilian criticism of the war was contributing to veteran suicides (post).

"Imagine a book in which every speech is “You Can’t Handle The Truth,” except Jack Nicholson is actually in the right, and also we’re supposed to want to fuck him." I had to stop reading when I got to this point because I was wheezing with laughter. It's easy to be caustic when writing about bad fiction; your relative restraint here makes your criticisms land even harder.

My main thought about this book, and its "I'm a fucking weapon" ethos, is that we really did do Isabel Fall dirty - this really does read like "...Attack Helicopter" minus the irony.

I absolutely lost it at "She is rechristened 'Violence' "

It is interesting how while literature has accepted "War is Hell", it usually gets presented as "War is Hell :smiling devil emoji:"