Happy Thanksgiving to Solomon Kane, Pulp Fiction's Unhinged Puritan

Robert E. Howard's God-fearing swordsman with a kill count in the thousands

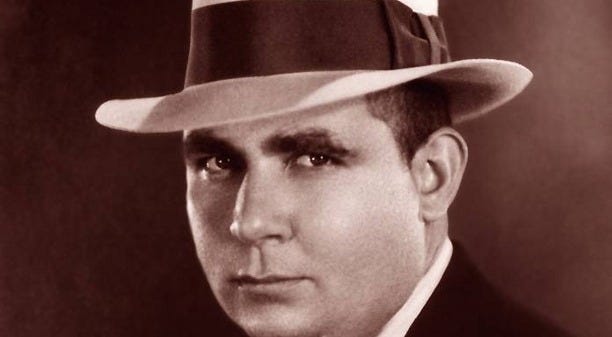

As a teenager, Robert E. Howard came up with the idea for a 16th-century swordsman. He wanted to write a hero of the “cold, steely-nerved duelist” archetype, and perhaps was influenced by the thrilling pirate histories that he was reading at the time.1

This hero would take years to gestate in Howard’s mind; in 1927, when a twenty-one-year-old Howard finally wrote him down, he had taken the form of a Puritan in black clothes with ice-blue eyes. Solomon Kane would appear in 7 published stories from 1928-1932, and over the course of his pulp fiction wanderings would kill an untold number of evildoers, totaling somewhere in the thousands.

Kane was introduced to the world in “Red Shadows,” the cover story of Weird Tales August 1928. “Red Shadows” has one of the best cold opens of any pulp story; its introductory vignette, a chapter called “The Coming of Solomon,” clocks in at 378 words yet contains shock after shock, escalation after escalation. Howard gives us outlines of our hero in a series of evocative, sparse details: a “long, slim rapier,” a “somber brow,” a “soothing” voice that belies his austere appearance. At the introduction’s close, Kane utters a vengeful line so hard you’d have to be flatlining on a gurney to stop reading.

Kane in Africa

After Chapter 2, “Red Shadows” takes a sudden dramatic turn. As Kane pursues the murderous brigand Le Loup to Africa, we’re introduced to the racial aesthetics that will come to play a central role in the saga. Howard’s ever-shifting thoughts on race, especially as it relates to themes of human destiny and “savage” truths about the universe, feature in the majority of Kane’s adventures. The four longest and most elaborate Kane stories are set in Africa, and with each entry Howard seems to be revising, expanding, and experimenting with the same questions about the stock environment of the Dark Continent: how “savage” are the natives? Is this “savagery” good or bad? How can deeper truths about the universe be accessed via “savage” religions and lifestyles?

The results are uncomfortable, seldom consistent. Howard ricochets, often within the same story, between Pulp-Africa cliches (human sacrifice, Jezebel temptresses), evolutionary Darwinism (a fixation on “stock” and racial destiny), and more progressive, egalitarian tropes (Kane becomes “brothers” with the witch doctor N’Longa, and Howard frequently remarks that good and evil have no skin color).2 The racial ethos underneath the works seems to shift at any given moment, depending on what feels most inspiring, shocking, or compelling for Howard or his imagined reader. The most extreme examples — fever dreams like “Red Shadows” and “Wings in the Night” — feel like a glimpse into the crucible where Howard’s inchoate, often disturbing, theories about race combined with his most basic creative impulses.

If there’s one consistent pattern throughout Kane’s African arc, it’s that Howard uses the “primitive” setting, with its jungles and tribes and predators, as a means of challenging Kane’s Christian self-image. Kane sees himself as an avenger following a higher power, but his fierce desires to spill blood and seek adventure belie these pretensions. The stirring air of Howard’s “Africa” only serves to whet these urges and reveal Kane as a “savage” in denial:

… the drums roared and bellowed to Kane as he worked his way through the forest. Somewhere in his soul a responsive chord was smitten and answered. You too are of the night (sang the drums); there is the strength of darkness, the strength of the primitive in you; come back down the ages; let us teach you… (“Red Shadows”)

The cliched “savage” environment gradually reveals the libidinal warrior beneath Kane’s high-minded pretentions of virtue.

Kane in Hell

While the racial aesthetics of the Kane stories register as dated, Howard’s depictions of Kane’s spiritual and existential crises still reads as innovative, even timeless. Unlike the stable, well-adjusted Conan, whose barbarian “roll with the punches” attitude allows him to respond to setbacks without distress, Kane finds himself pushed to the limits, spiritually and mentally. Where Conan bends, Kane snaps; the kinds of revelations that would be par-for-the-course in other weird tales (pre-human civilizations? eldritch terrors from outer space? outer space?) take an outsize toll on the poor Puritan. When confronted with a new creature or mythic setting that challenges Christian cosmology, Kane usually responds with repression,3 then realization, then crisis. In “The Footfalls Within,” after battling an obscene ancient entity,

Solomon Kane shuddered, for he had looked on Life that was not Life as he knew it… Again the realization swept over him… that human life was but one of a myriad forms of existence, that worlds existed within worlds, and that there was more than one plane of existence. The planet men call the earth spun on through the untold ages, Kane realized, and as it spun it spawned Life, and living things which wriggled about it as maggots are spawned in rot and corruption. Man was the dominant maggot now. (“The Footfalls Within”)

The final completed Kane tale, “Wings in the Night,” pushes Kane’s existential terror to a hysteric pitch, in which Kane fights alone, surrounded by the corpses of both monsters and the people that he’s failed to protect. At the height of his anguish, Kane breaks from Christianity completely, overcome with rage and helplessness at the true nature of the universe.

He cursed the cold stars, the blazing sun, the mocking moon, and the whisper of the wind… In one soul-shaking burst of blasphemy he cursed the gods and devils who make mankind their sport, and he cursed Man who lives blindly on and blindly offers his back to the iron-hoofed feet of his gods. (“Wings in the Night”)

Kane’s journey brings him to a nihilism and hopelessness that we know sometimes plagued Howard as well. Religiously speaking, Howard was largely agnostic, and in his darker moments, this agnosticism left him with a pessimistic view of nature and man’s ultimate unimportance. “That life is chaotic, unjust and apparently blinded without reason or direction anyone can see,” he wrote to a friend. “If the universe leans either way, it is toward evil rather than good.”

The violence and upheaval of the 1930s sometimes triggered Howard’s melancholia. Just as Kane is unable to bear the true face of reality, Howard himself felt overwhelmed and remarked that the reassurances of a religion or “faith” might have helped.

Where can a man turn? I wish I had vision, or a fanatical faith in something or somebody that creates an illusion of vision.

The “illusion of vision” and return to the comforting illusion of faith is a recurring beat that happens at the end of most Kane stories: Kane pulls back from the precipice of existential despair and reverts to his Puritan programming. Biblical verses spew from his lips and his faith in Providence returns, often accompanied by light from the sky. As the horror of the episode fades like a bad dream, Kane is able to journey on and safely process what has happened to him in Christian terms. Given what we know of his complexes, we’re obviously meant to recognize this as denial: each time, Kane’s Christian credos seem shakier and shakier, and his divine ecstasies feel more and more like desperate performances. It’s the only way he can cope with the true horrors of cosmicism.

The narrative poem “Solomon Kane’s Homecoming,” which bookends the African cycle, make it clear that Kane, as much as he would like to, cannot re-integrate into Christian society. He’s been irrevocably changed by the eldritch darkness, and if he finds lasting peace anywhere, it will be out there.

Share with a fantasy/history fan who also finds this stuff interesting!

A Tier List of Kane Stories + Links for Reading

Several of the tales are not on the Internet/not public domain everywhere. When a full story was not available, I linked a sample. The Solomon Kane Omnibus from Benediction Classics has many of the stories, as does The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane. The site Robert E. Howard World keeps information on each story (link here).

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED (AGED WELL)

“Rattle of Bones” (1929) — 10/10. Solomon Kane befriends the flamboyant French adventurer Gaston l’Armon and they sojourn at a tavern that turns out to be the medieval equivalent of Comet Ping Pong Pizzeria. Kane’s autistic single-mindedness comes through exceptionally in the buddy comedy parts.4 The villain has a great backstory and everyone gets their comeuppance.

“Blades of the Brotherhood” a.k.a. “The Blue Flame of Vengeance” (1929) — 8/10. In its original form, it was rejected from Weird Tales, likely since it had no speculative element. (Howard had written the first Kane story, “Red Shadows,” specifically to appeal to WT.) “Blades” takes place on the English coast, and has an earthy, swashbuckling feel. Howard clearly relishes in the Shakespearisms (“meseemeth”) and period details (rapier and dagger). The fight scenes are insane.

“The Right Hand of Doom” — 9/10. We’re back in England. Kane impales a hand of glory on his sword. Say what you will about Howard, but the felicity with which he can mock Elizabethan dialect is unexpectedly stellar.

“The Footfalls Within” (1931) — 8/10. Kane sets out to liberate a slave train in a vaguely Arabian setting. We learn that he harbors an “unquenchable hate” for the slave trade, informed by his own traumatic past spent in the underbelly of a Turkish galley. “Footfalls” begins a series of innovative stories in which Kane starts to lose his cool, and Lovecraftian elements are introduced that challenge his Christian cosmology.

“Solomon Kane’s Homecoming” (dramatic poem) — 8/10. In this poem, Solomon Kane returns home to shadowy, windswept Devonshire. He describes his adventures and considers settling down… then inevitably disappears into the ghostly fog off in search of more adventure. “His eyes were mystical deep pools that drowned unearthly things.”

OF SCHOLARLY INTEREST (PROBLEM WORKS, KANE IN AFRICA)

“Red Shadows” (1928) — 5/10. Notable for being the first published Kane story. First and second chapters: some of the finest fantasy prose and character studies put to paper. Chapters after they leave Europe: yikes

“The Moon of Skulls” (1930) — 3/10. We’re back in Africa, this time with a bisexual vampire temptress. For the first half of the story, Howard is writing on autopilot as far as tropes go. Kane’s discovery of a lost race of “brown” Atlanteans whose capacities are far beyond “white savages” makes for an interesting twist, but Howard ruins it by drifting back into themes of miscegenation and cultural decline. Starting each chapter with a quote from G.K. Chesterton is a choice, though by the end Howard is doing something clever and almost ironic with them.

“Hills of the Dead” (1930) — 4/10. Kane goes on a quest with his “blood-brother” N’Longa, a voodoo sorcerer, to destroy a city of vampires somewhere in Africa. Still egregious, but you get the sense that Howard is earnestly trying to attempt a devoted and equitable white-black friendship, albeit one heavy with magical Negro tropes.

“Wings in the Night”(1932) — 6/10. On one level, it’s Solomon Kane vs. the Mothmen. On another, it’s the most innovative, problematic, and disturbing entry in the saga. Kane befriends an African village and defends them against akaanas, winged monstrosities that originated in “the world’s infancy when Creation was an experiment.” This story is intriguing because Howard seems to be actively evolving the cliched Pulp Africa setup he’s written himself into. For one thing, the villagers are depicted as profoundly normal people, varied in manners and personalities; Kane speaks their language and lives with them happily for several months. The “savage” element from earlier stories is assigned to the non-human (or alternately human) akaanas. Chapters 4-5 depict a harrowing subversion of the white savior trope that, while ghastly in its own ways, represents a huge rift from the previous entries of the story in terms of scale and consequences; Kane barely escapes with his sanity. When Howard concludes that “over all stands the Aryan barbarian, white-skinned, cold-eyed, dominant, the supreme fighting man of the earth,” the vision feels hysteric and grim rather than purely triumphant. What does it mean to dominate a world submerged in flames and carnage of one’s own making?5

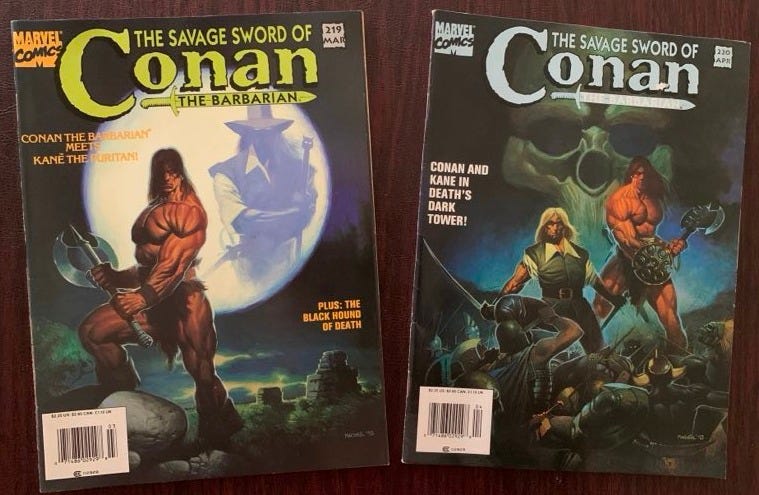

They worked it out on the remix! From my personal collection: Conan and Kane in Savage Sword #220-221, Mar/Apr 1994. Covers by Colin MacNeil. Their adventure is a sequel to “The Moon of Skulls”; Ben Herman writes about it here.

NOT REMARKABLE

“Skulls in the Stars” (1929)— 2/10. Meh. There are some elements that feel Lovecraft-inspired (spectral fungus), but Howard over-explains Kane’s motivations and strips away some of his mystique. Improves in the second half.

“The One Black Stain” (dramatic poem, unpublished until 1962) — 3/10. We get some lore on Solomon Kane’s history with Francis Drake. Not special in any way.

“The Return of Sir Richard Grenville” (dramatic poem) — 4/10. It’s carried by the unbelievably hard line “The hounds of doom are free.”

FRAGMENTS/RELATED WORKS

“Death’s Black Riders” (fragment) — adapted into a comic by Dark Horse

“The Castle of the Devil” (fragment) — adapted into a comic by Dark Horse

“The Children of Asshur” (fragment)

“Hawk of Basti” (fragment)

Solomon Kane the movie (2009): You thought I wouldn’t include this masterpiece? You thought you could get away that easily? Fools!

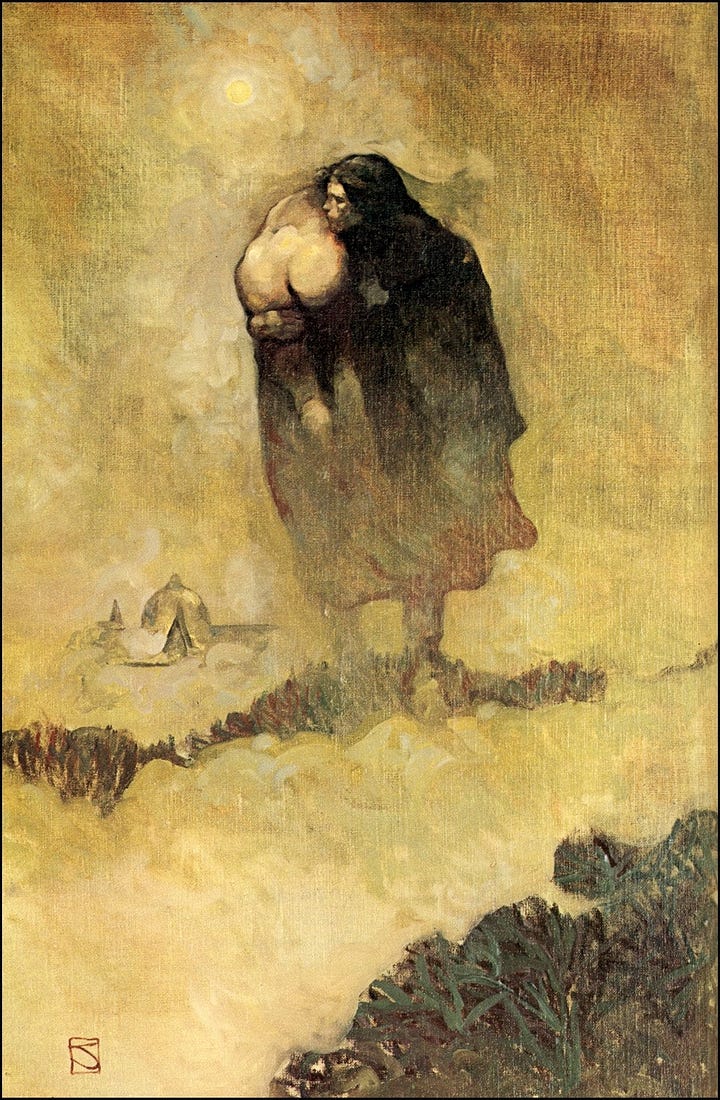

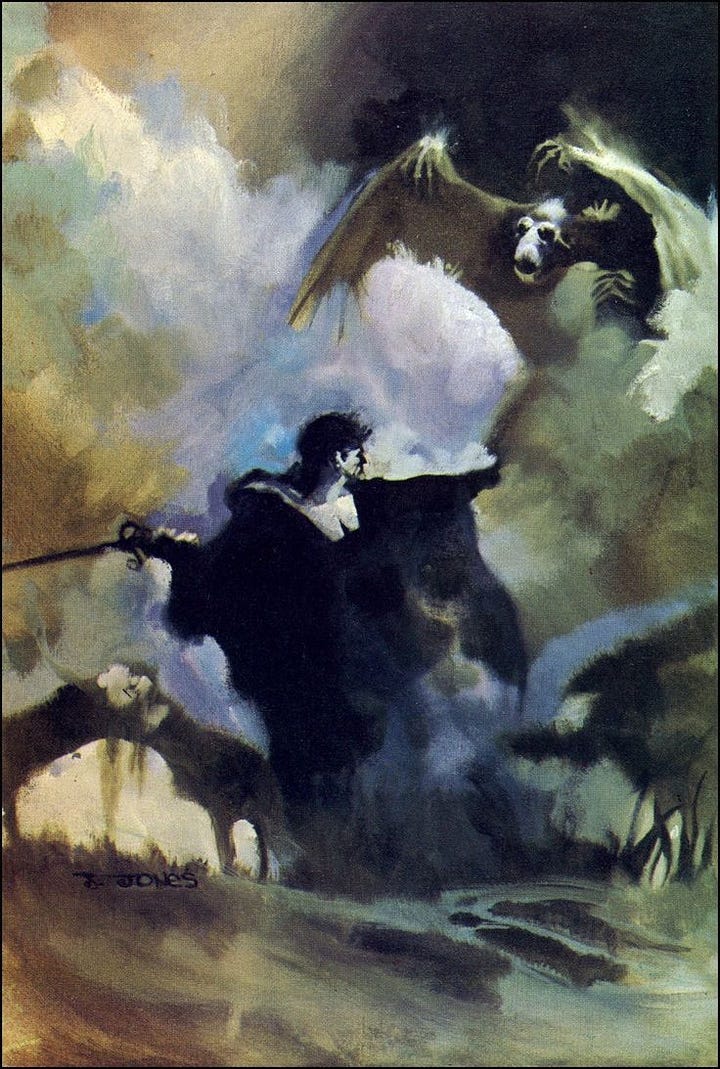

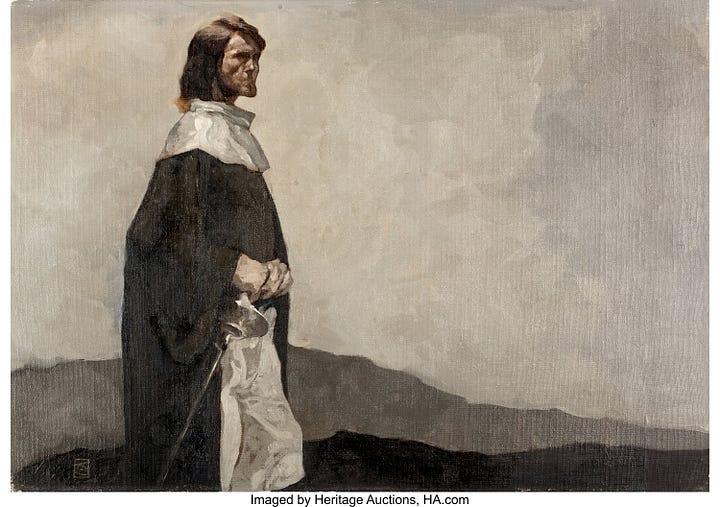

My favorite art of Kane is probably by Jeff Catherine Jones. It honors the primordial atmosphere with broad swaths of darkness and light, and depicts Kane as a wavering, half-formed body that emerges from Turner-esque murk. My favorite is probably the painting of Kane shouldering a naked woman, which uses an otherwise raunchy pose to demonstrate Kane’s unexpected austerity and remoteness in classic S&S situations.

The name “Solomon Kane” might have perhaps originated in a Western story in Adventure, read by the teenage Howard. A character of the same name from 1923 was rediscovered by Kurt B. Shoemaker, the ties to Howard/Kane are noted by Todd B. Vick.

Howard’s personal beliefs on race, as expressed across his life, seem equally nebulous and difficult to write about in any concise way. His racist anxieties are certainly documented in correspondence (especially with Lovecraft), though there are other instances in which he gestured toward black heroism or general vitalist equality. (In fact, in a recently-discovered letter announced 5 days ago, Howard expresses how cool it would be to have Mongolian heritage, and admits that for a while, he wanted to believe he was descended from Muhammad.) This is a man who wrote in glowing terms about Black slaves murdering their captors in The Hour of the Dragon, then wrote “Black Canaan” within a year.

Howard was aware of Freud, and the “Puritanism” of Solomon Kane often feels like a metaphor for the superego: an intellectual structure that makes man conceive of himself as a higher, more refined being; notions of “Providence” and God’s law function as an elaborate cover for Kane’s urges to kill and punish.

Howard speaks disdainfully of the superego. In his writings about snakes, he associates it with subtlety and the flaws inherent in civilization: snakes have a “super-ego that puts them outside the pale of warm-blooded creatures.” The conflict of cold intellect vs. warm animal urges is a core aspect of Kane as well.

When they’re shown to their room, Kane suggests, straight-faced, that they break down the table to barricade the door. l’Armon, naturally, is like “what the fuck is wrong with you”

It’s interesting that in his letters, Howard wrote that he did not believe in the “eventual Superman” which he deliberately seems to be evoking here.

Interesting character! Enjoyed reading your post and learning about Mr. Kane.

Man, I like that film way more than I should. Probably something to do with James Purefoy being crucified in a sopping wet black shirt, but we take our pleasures where we can get them.

This is a really helpful round up, thanks.