Make Sci-Fi Cringe Again (Duneposting 1)

Comparing film versions of sci-fi's weirdest, greatest, cringiest crown jewel

The other night, a friend and I went to an anniversary screening of David Lynch’s 1984 Dune. Its manmade horrors were consumed in the way God intended: on a towering screen, with a printout of the infamous Dune Terminology sheet balanced in my lap, as I inhaled a bucket of curly fries agleam with twice their weight in grease. Visually, Dune is an orgy of delights: a dense mannerist universe filled with gilt and wires and inbred animals/people. The voiceovers are camp, the editing ridiculous, the hairdos lofty and aggressive (Aquanet — like spice — must flow). Around the midpoint of the movie — when Sting slinks out of a sauna in a codpiece —the audience had come to the unspoken understanding that it was okay to laugh instead of sitting in respectful, cinephilic silence. The Harkonnen milking machine (i.e. a rat just duct-taped to a cat) brought down the house.

After the movie, we took an elevator down. There was a woman next to us, talking to someone on the phone and giving her post-mortem on Dune. She said her “assessment of it” had changed for the better. But what infuriated her had been the audience — some people had been laughing audibly during the movie. My friend and I stared at the elevator buttons and made our awkward exit, trying not to look like laugh-havers who’d just spent the past few hours tittering and crying and choking up organs.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the elevator woman since then. She was right about assessments. Dune ‘84 is a highly underrated film, a visionary freak that, every few years or so, seems to demand its own cultural and critical reevaluation simply by existing. Her second point — that how dare people laugh, that a reevaluated Dune deserved better than that — was way more interesting (or maybe I’m just using Substack to further my own denial about ruining other people’s nights at $20 movies).

Seriousness and respectability have been a constant theme in discourse about Dune adaptations, probably because Lynch set the bar for dignity so low. When it premiered in ‘84, a few rare people liked it, many more people loathed it, but almost nobody took it seriously. Roger Ebert generously offered that “the only thing you could possibly do with [Dune] is use it as a talk-back movie… on the campus circuit.” “Hoot at it,” Siskel agreed.

Compare that to Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part 1, which pulls a hard reverse into complete dead-seriousness and visual conservatism. That film — part of a duology that’s pretty much destined to become the definitive adaption of Herbert’s book — takes great pains to avoid any potential for the awkwardness and embarrassment that plagued its predecessor.1 Every weird burr from the novel has been shaved away, especially those elements that might remind us of the Lynch version: the characters’ internal monologues, the pustular body horror, the sumptuous set decorations. Where Lynch heaped plenitude, filling every shot with epaulettes and goop, Villeneuve seeks a void: large tracts of fog, dust, and sand, negative space onto which figures can be judiciously arranged, and which guarantee the CGI will always look atmospheric and awe-inspiring.

Every plane and surface in the Villeneuve Dune is calculated to be taken seriously: muted color grading, sleek spaceships, generic FPS-style armor that communicates a vague, formidable masculinity.2 The Harkonnens are presented as stern, intimidating creatures, stripped of their gleeful hedonism, bleached of color itself. Spice appears as a tasteful red bokeh effect, a barely-there breeze of fiery snowflakes — certainly not as the symbolist, Abel-Gance-esque hallucinations of the Lynch film. Hans Zimmer’s booming score is full of all the grim sounds we associate with serious movies these days, with ominous drones and bwaaaahs, plus some female ululations and duduks because Desert. When all is said and done, Dune: Part 1 is really the peak filmbro movie: Zimmer-maxxed, epic but cerebral, full of perfectly-constructed, “cinematic” moments. Space Oppenheimer.

In his review, “The Mouse That Jumped,” Henri de Corinth mentions that during the publicity for Dune, the Villeneuve cast was instructed to “speak away” from the novel fandom; instead, the overall goal has been to give the impression that Dune is an accessible, cool thing that normal people can enjoy without, like, lava lamps and autism. To the studio’s credit, this is probably the only way to make of Herbert’s Dune a truly massive blockbuster, a critical and commercial phenomenon that can transcend the 1984 disaster, your date movie and also your parents’ date movie, an Oscar-worthy masterpiece at which no goblin with a Substack would ever heh-heh-heh while deepthroating curly fries. The issue is that at that point, your connections to Herbert’s Dune are plot-based — the aesthetics, the sensibilities, the essential weirdness of the project are diluted, often to the point of not being there.

I’ve been re-reading Dune to prepare for the Villeneuve’s Dune: Part 2, and am surprised that (1) people out there still claim that Frank Herbert was bad writer, and (2) it’s a lot funnier than I remember.

(1) is easy to explain: the “bad writer” accusation is a kind of backlash Tolkien gets as well, in which readers (especially those who loved the books uncritically as kids and return in adulthood) apply our loose contemporary norms of “beautiful writing” to a work whose sensibilities lie in a completely different place. I’d define the current standard for “good writing” in genre fiction as vaguely graceful/lite-lyrical (your Madeline Millers and Patrick Rothfusses), with a lot of emphasis placed on the relatability of characters and their arcs; worldbuilding should be carefully phased in and never too overbearing; narrative voice should be lucid and readable. Dune is none of those things. It’s a stilted beast whose style abruptly changes from character to character and section to section (Herbert compared his own writing to jazz, and being “pleasing to the ear” was secondary to him). Its worldbuilding is an information firehose on full blast that never turns off. And, basic hero’s journey stuff aside, who really relates to Paul or his surrounding figures? Dune’s characters are all, per

’s recent piece, weird little freaks running around like mice in their cognitive mazes. The book was never conventionally graceful or concerned with seeming so — it was intricate and perfectly-controlled in other ways.Which brings me to (2): Dune is hilarious. Frank Herbert had a keen sense of dramatic irony, and seems aware that the entire concept of “humans conquer space yet are somehow still doing Masterpiece Theatre shit” is pretty funny. There’s a kind of Barry Lyndon quality to the whole novel: a tragic plot inhabited by strongly comedic characters, unaware of their own limits and banality. Some are outright hoots (Piter de Vries, the messiest queen in all of science fiction3, and Gurney Halleck, a minstrel-soldier who really likes singing about tits), while others get more quietly embarrassed. Even the most formidable antagonists have some deflating, petty traits — Reverend Mother Gaius Mohiam is a Lady Bracknell type, snarky and stuffy; Baron Harkonnen is neurotic, bombastic, and addicted to his sybarites. Herbert undercuts the noble, tragic air of House Atreides with subtle, unflattering insinuations about their competence: although Duke Leto is revered by his family (and their chronicler-simp, Princess Irulan), his naive qualities are obvious from the start, and the other imperial factions pretty much agree that the Atreides patriarchs have always been idiots. Herbert doesn’t exactly do much to disprove this notion — he simply lets the beats speak for themselves. The fallen Old Duke, an amateur matador, is such a funny motif precisely because the Atreides take him so seriously:

Mapes crossed to the bull’s head… “I’ll have to be cleaning this first, won’t I, my Lady?”

“No.”

“But there’s dirt caked on its horns.”

“That’s not dirt, Mapes. That’s the blood of our Duke’s father. Those horns were sprayed with a transparent fixative within hours after this beast killed the Old Duke.”

None of this makes it through to the Villeneuve film, which ensures that its villains are weird and gross, and that its heroes are virtuous and hot, but that nobody’s presence is ever amusing. For to be amusing is to be vulnerable, and to be vulnerable is to be uncool, and both a risky territory in a prestige film. Take Duke Leto, for instance. In Lynch’s version, he (as Jurgen Prochnow) comes across as noble but foolhardy, overconfident in his political gamesmanship — a portrayal that rings pretty close to the book. In Dune: Part 1 (as Oscar Isaac) Leto is upgraded to a generic sigma: stern gaze, iron jawline, commanding presence. He walks Paul through their ancestral tombs and instructs him about family honor and legacy; the script dutifully sidesteps any mention of grandfather’s insane bullfighting accident. Even when he’s defeated and stripped naked by the Harkonnens, Leto remains dignified — sculptural, spartan, in one of the best ass scenes in cinema — and dies with a Luther-esque “here I remain” on his lips. The other supporting characters (like Piter, Halleck, the Baron) are similarly sigmafied and purged of their respective cringe factors and little quirks, because god forbid anyone be entertained by these characters instead of perpetually impressed by them.

Another thing that’s carefully controlled in the Villeneuve film is the language: dialogue is sparing, terse, naturalistic. It’s pretty classy all-around; I really don’t have notes to give. There are no notes to give. If someone tried to fit a hundredth of the dense, scattershot language of Dune into a mainstream movie, the result would probably induce an aneurysm. David Lynch approached this threshold, trying to honor Irulan’s epistolary interjections, and it produced some of the greatest, strangest cringe in history.

But should cringey dialogue really be so intolerable in a Dune movie? In the novel, Herbert’s prose worked on advanced levels of irony and calculated gags. So many of the terms and phrases of 10,191 A.G. sound natural to the characters but risible to us (mention “Duncan Idaho” to a nonfan and see how they react). There’s the Orange Catholic Bible, na-Barons and pru-doors, family atomics, tents with sphincters, and a random Fremen warrior whose name is just Geoff. The continued existence of cheddar cheese some 20,000 years from now is confirmed on page 258.4

It’s all quite funny, until — in Herbert’s true alchemical fashion — it becomes weirdly profound and awe-inspiring, a bric-a-brac sculpture formed by millions of minds over vast lengths of time. Words have merged, evolved, lost meanings and gained others. Some survive for long-lost, unknowable reasons. The beauty of Dune Terminology is something you can only appreciate after you’ve fully passed through the cringe, bathed in its waters.

Same with the ‘84 Dune: for all the awfully bathetic moments, there are many shots and visuals that evoke genuine awe. It remains inimitable to this day.

Dune: Part 1 is nice. I will never not concede its merits or its artistry or what it means as a technical achievement. Like Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, it filled a need for many fans, which was to have — after a long redemptive journey — a film version of a much-loved book that checks every box of coolness, respectability, prestige, and badassery that we as nerds wish to assign to ourselves. I’m looking forward to seeing Part 2 in all its shades of beige and having my brains pulped against the wall when that Hans Zimmer music hits the subwoofer.

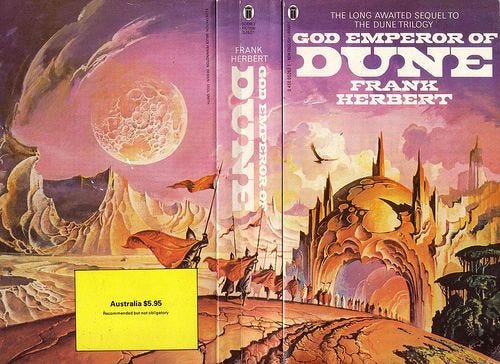

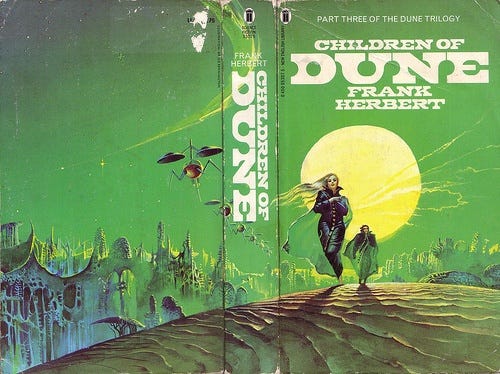

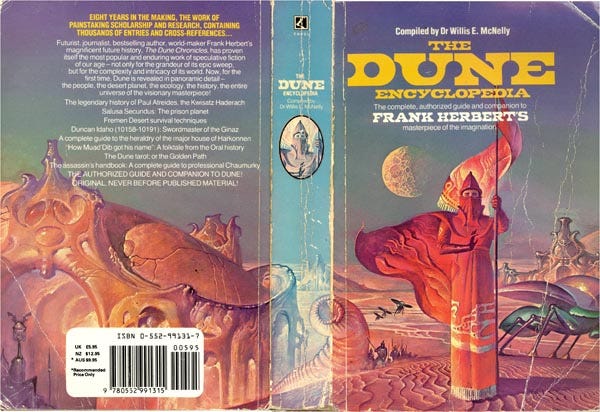

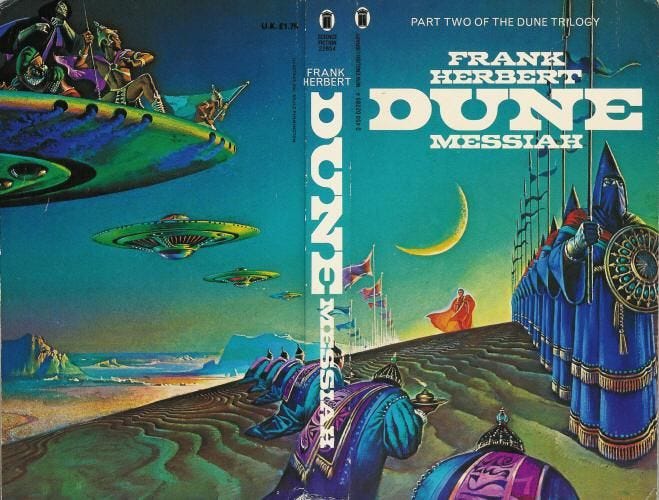

Like an unfaithful lover, I will be thinking of Dune ‘84 the whole time. And probably the Pennington paperbacks as well.

There’s been a lot of discourse recently about revivals: sword-and-sorcery revivals, new New Weird, pulp, horror, returns to zines and small presses and decentralized publication. In a few years, when corporate fantasy and the IP bubble run their course, people will need to flee towards something that is truly alien and new and challenging. A true paradigm shift has not happened in SFF for a long time (fight in the comments, etc), but when it does, it will probably be something in the vein of Dune: a bizarre, ambitious project completely unconcerned with our present aesthetics of respectability and coolness. It will embrace the risks of being laughed at.

The cringe must flow.

Yes, I’m aware of the syfy show. I’ve, uh, tried to watch it

Henri de Corinth, in a review far more intelligent than this one, identifies the Villeneuve Dune look as part of the dominant aesthetics that define “prestige genre filmmaking” today (see Villeneuve/Nolan/sometimes Ridley Scott). It’s a school of Hollywood cinematography indebted to Eastern Bloc sci-fi, defined by austere sleekness and “minimalist, quasi-Brutalist, moderne environments, rendered in a clinical palette with a limited color range.” In his piece, Corinth also discusses how this aesthetic made its way stateside in the 90s, when an influx of Polish cinematographers raised on Soviet sci-fi carved out a space in Hollywood.

Played in Lynch’s version by Brad Dourif, who would bring the same A-game to Grima Wormtongue in Lord of the Rings.

Note: a correction was made here regarding Dune chronology. See comments

Another fun fact about the original - soundtrack by Toto. Loved to have heard that discussion! “Let’s see if Toto is available”

Nice post, but one big correction. ;) It's not 10,191 AD = 8,000 years from now. It's 10,191 *AG* as in After Guild. The Guild was formed after the Butlerian Jihad, which itself is about 10,000 years in our future. :)

This fan page explains the timeline: https://dune.fandom.com/wiki/Universal_Standard_Calendar

P.S.: sorry if this comment gets posted several times: Substack's system for new commenters is remarkably user-hostile haha